In 2019 and 2020, UNV reported achieving a 50-50 gender balance among its men and women volunteers. This is an admirable feat and sets a good foundation for moving towards gender equality. But the work does not end there. We also need to look at the hidden figures and go beyond averages to better understand and uncover intersectional disparities.

Are these numbers more or less the same across regions, age groups and types of volunteering work? Are women and men volunteers getting the same recognition for the same types of work? And how can disaggregating such data help us better address gender differences in volunteering?

What do the hidden figures tell us?

Looking beyond averages will tell a slightly different story about how we fare with achieving gender balance in volunteering - at UNV and at the global level.

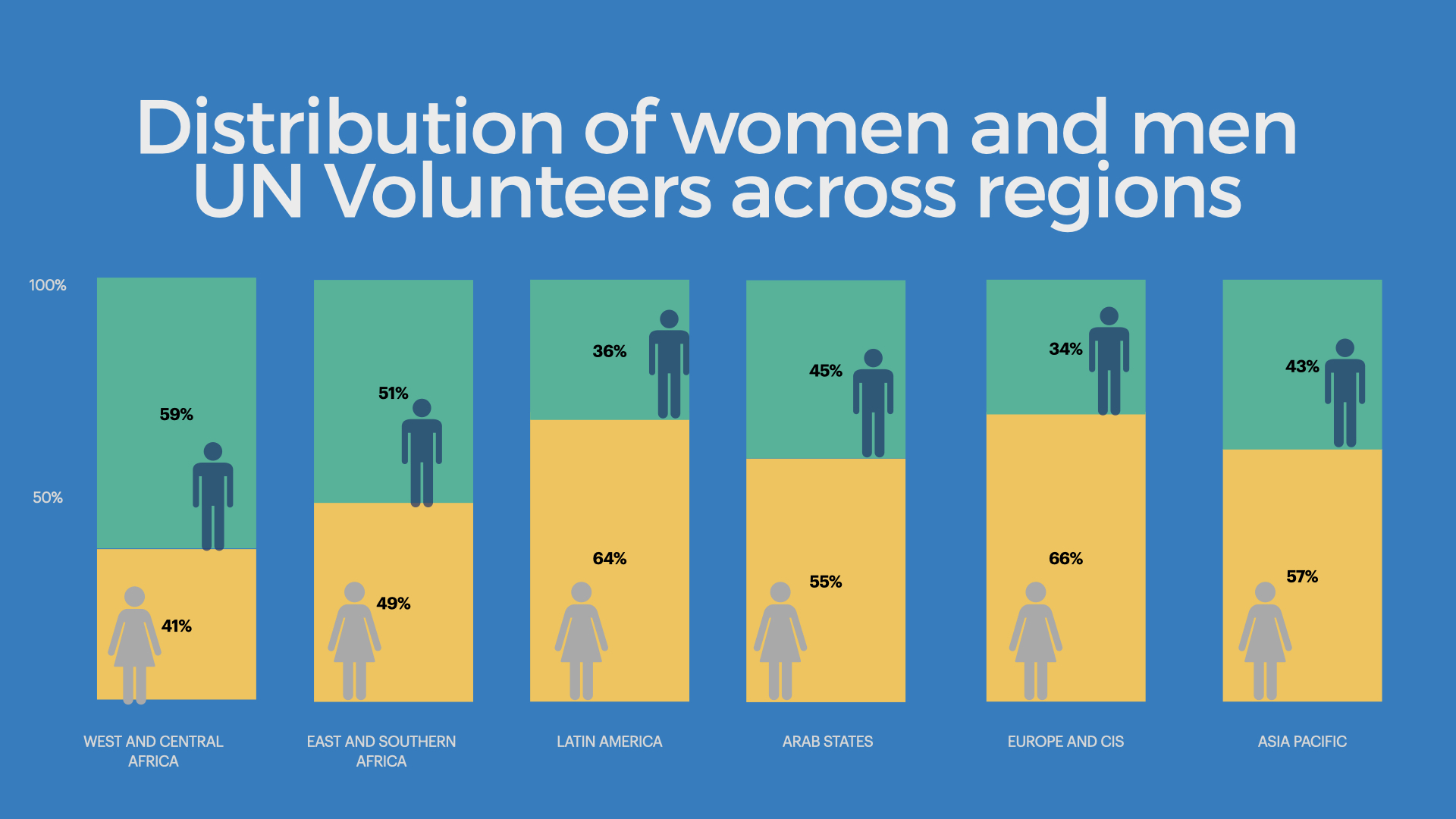

For example, if we disaggregate data on UNV gender averages, we will see that in some regions such as in Western and Central Africa, the average drops to 40-60 in favour of male volunteers, whereas in Latin America, the number of women volunteers tend to be higher.

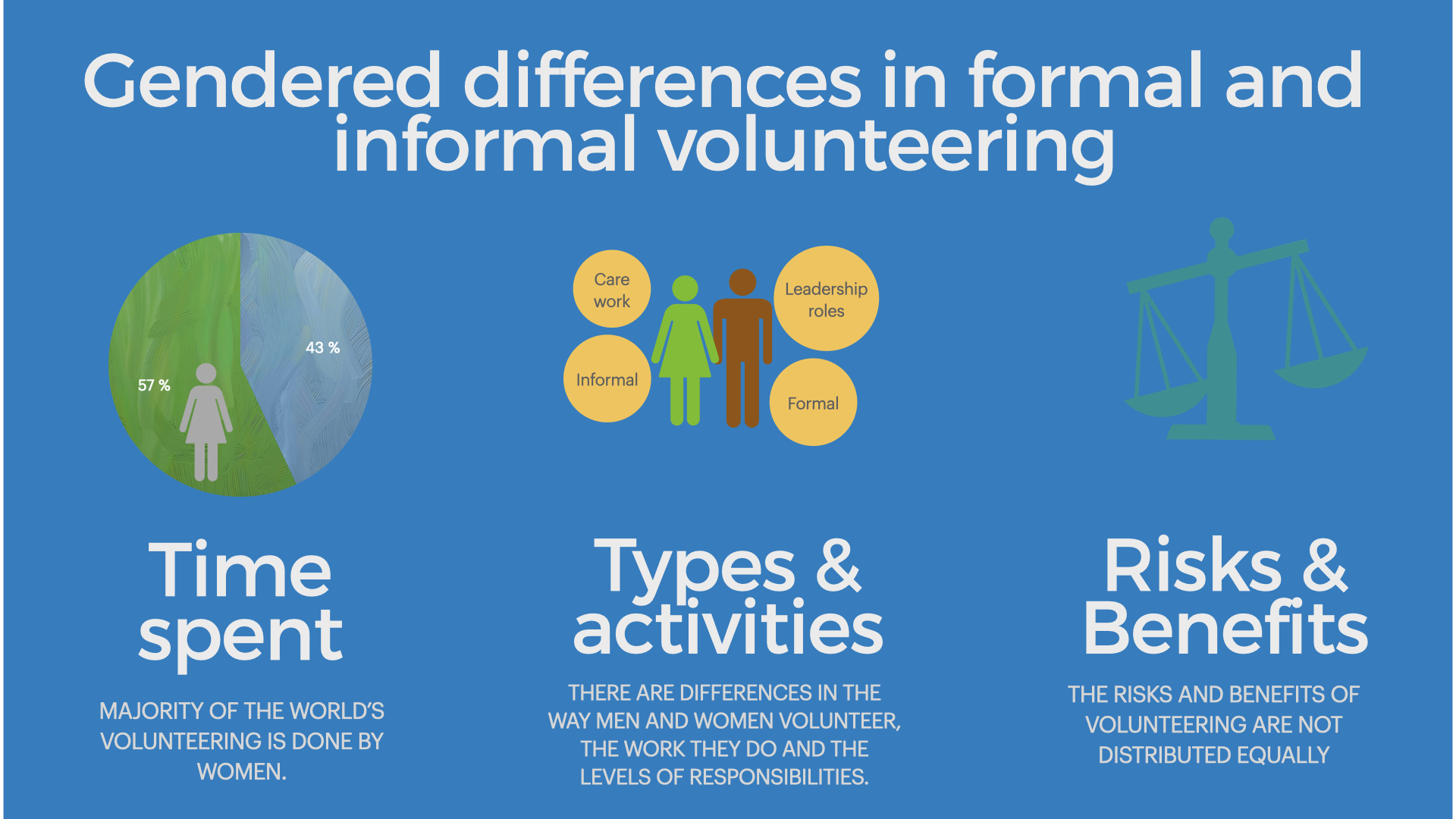

At the global level, if we consider all other types of volunteering, UNV’s research shows that women take on the majority of volunteer work, at around 57 per cent. Their share is increased when looking only at informal volunteering, 59 per cent of which is done by women.

Because volunteering is done by and between people, there are differences in the way men and women volunteer, the amount of time they spend, the types of work they do and their levels of responsibilities.

For example, just like the global labour market, volunteering roles can be highly segregated. Research shows that women are more likely to volunteer for organizations in the areas of social and health services, particularly unpaid care work beyond the household, while male volunteer participants are often found in political, economic and scientific fields.

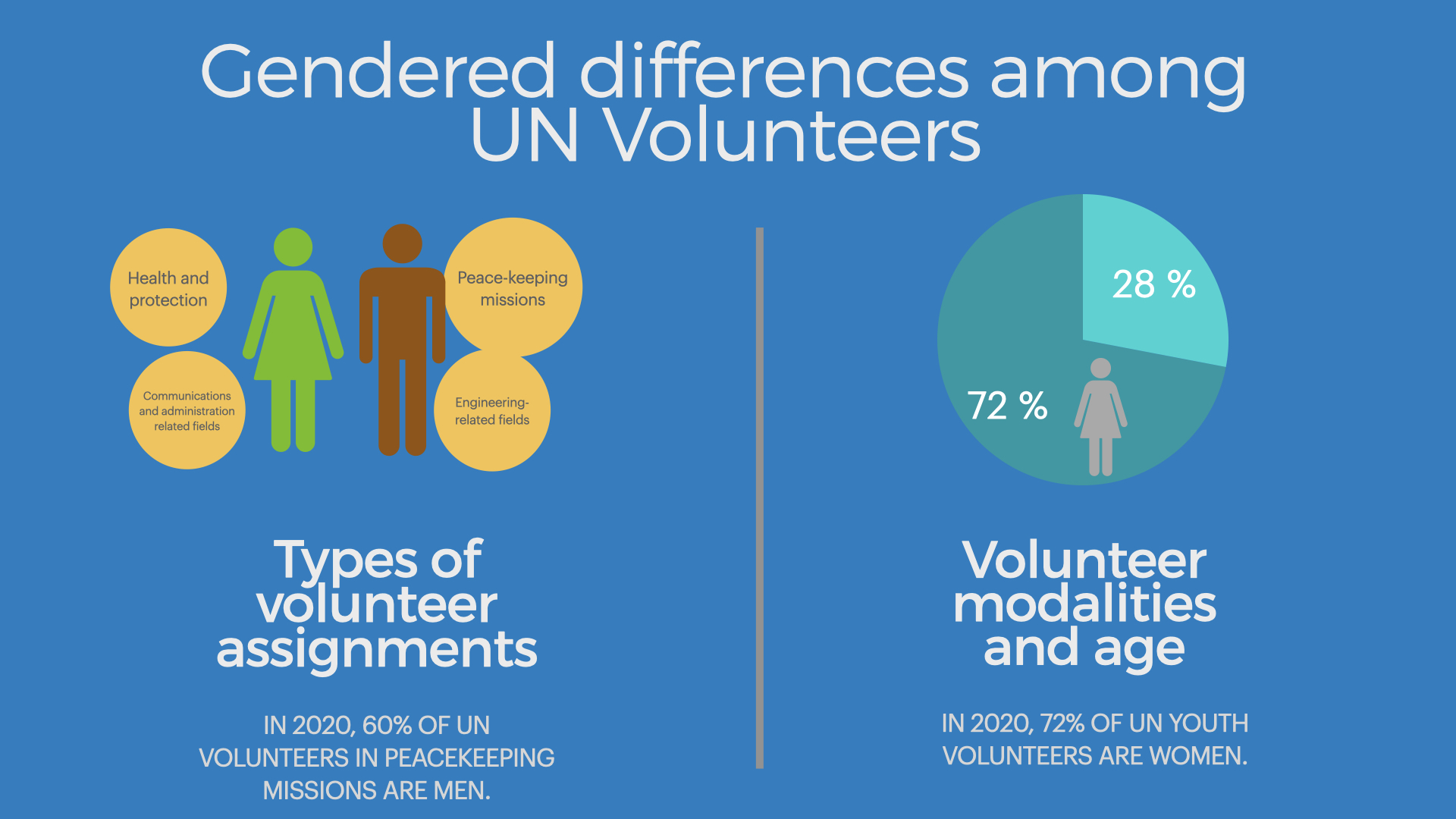

Further drilling down into the UNV figures suggests that certain volunteer roles such as in engineering and in peacebuilding missions are still highly male-dominated.

These differences are not natural occurrences. Nor is it in part due to lack of efforts from the part of UNV. Our teams have been hard at work to achieve gender balance across different fields, exerting extra efforts to get more women to apply to roles that are more commonly male-dominated.

Rather, these differences could be mirroring existing social norms and structural inequalities in our societies. What this means is that if we want to achieve gender balance in volunteering, we need to do more than getting more women to volunteer, we need bigger, systemic changes.

Beyond averages – so what can we do now?

Gender disparities can reduce the potential capacities of women and men to contribute to development efforts through volunteering.

From a policy point of view, it is important to understand what, where and how these disparities occur to better design policies and interventions that can address discrimination and inequalities.

One way to start is by investing in statistics. Improving gender-disaggregated data is crucial for understanding any gender dimensions of volunteer work.

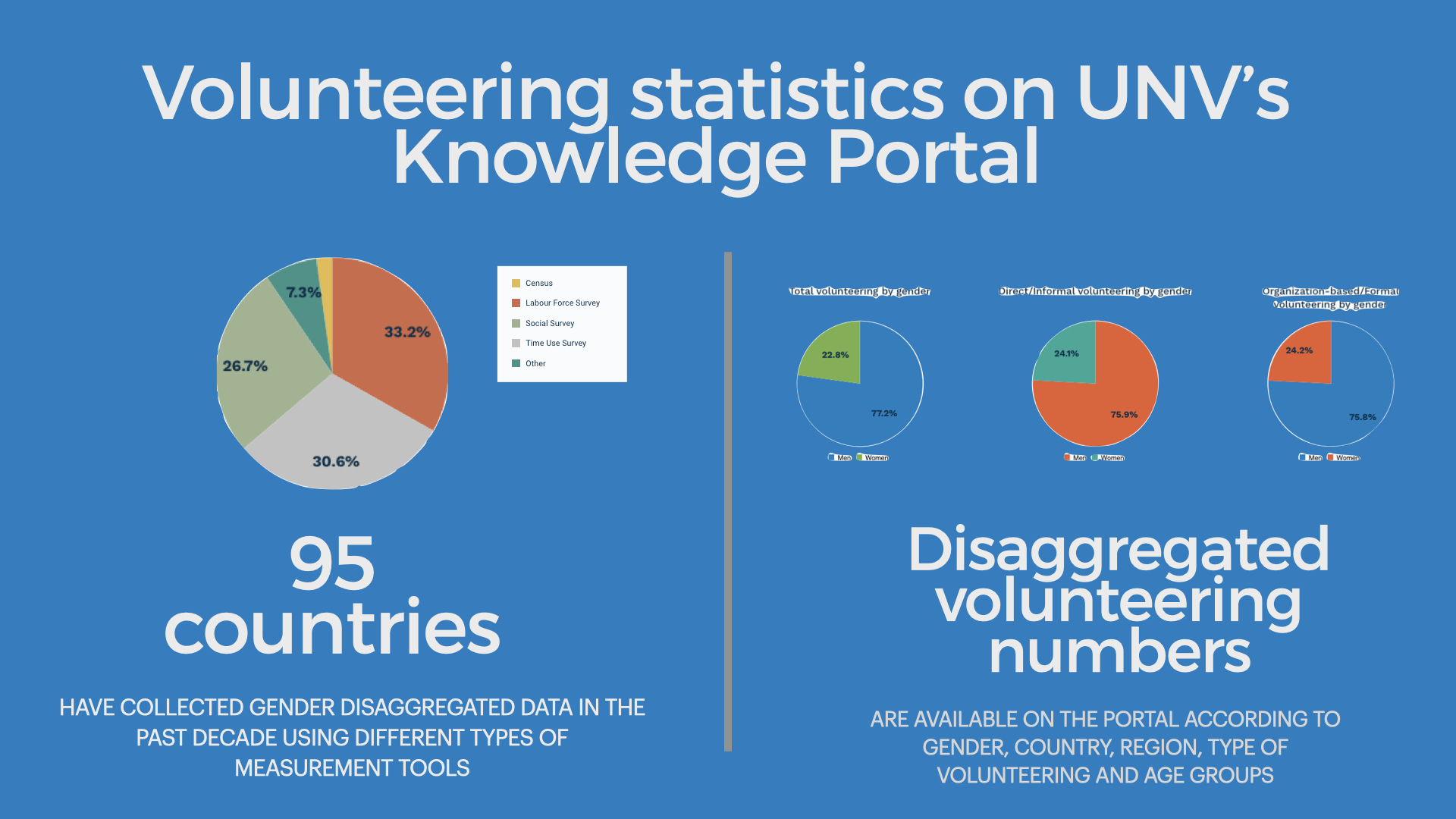

UNV, for instance, has greatly improved its data collection and analysis methods, ensuring that its volunteer numbers are disaggregated by countries, regions, age, gender and other indicators.

Globally, over 95 countries have collected gender-disaggregated data on volunteer numbers. Some of these are published on UNV’s Knowledge Portal.

National statistics agencies can collect data on volunteer work using Labour Force Surveys, rapid surveys and population censuses. When questions on volunteer work are included in nationally representative surveys, demographic data on age, disability and ethnicity can be explored in addition to gender, thus allowing for a better understanding of volunteerism inequalities.

Get started with UNV’s gender toolkit

Measuring volunteer work and disaggregating data is just one entry point for achieving gender equality in volunteerism. There are other important considerations such as expanding spaces for women participation and leadership, listening to different voices especially those furthest left behind, addressing strategic gender needs, and many more.

UNV recently published a new toolkit to help policymakers consider how to construct an environment for volunteering that is conducive to equal rights and opportunities for all, regardless of gender, income, ethnicity, disability, age or any other personal characteristic.

The road to gender equality is long and difficult - but not impossible. UNV seems to be on the right track and is ready to do more.

---

About the author

Katrina Borromeo is a Programme Specialist on Knowledge and Outreach at UNV. She manages UNV’s Knowledge Portal and actively works to better integrate gender concerns into UNV's evidence and policy work.